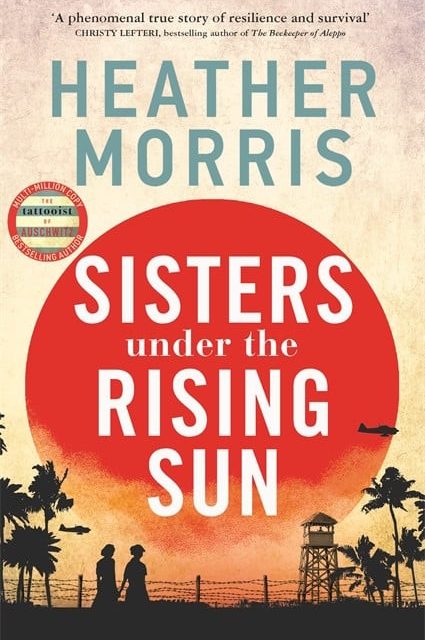

When the ancient scholars were defining the term ‘literature’, they must have had a foreshadowing of this truly superlative work by Morris. While it is not a masterpiece because it is a work of non-fiction, it is about as close as one could possibly get. And it is so for a myriad of reasons. In fact, if literature was rated on a scale similar to Sumo wrestling, this work would be ranked an Ozeki which is the second highest rank after the title of Yokozuna. It is so well crafted as to mimic a glorious, magnificently layered, expertly made Damascus Samurai sword with the narrative and its various themes melding together in a metallic tapestry that is simultaneously moving, emotional, educational, moral, courageous, victorious, inspiring and ultimately, timeless. The result is book that effortlessly slices through your psyche the way the newly made blade would slice through paper.

The title itself is a double entendre in that it refers to both female siblings and also nursing sisters who are quite literally pressed together by circumstances in the cauldron of war that was the Japanese conquest of South East Asia. It is in this pressing together that the book gains much of its themes and what I believe to be its modern-day relevance, despite being a work of historical non-fiction. There is a tertiary definition of the word ‘sisters’ in the fact that there were Catholic nuns present in the camp and they too come to represent a theme which in times of hardship is especially relevant to women through the ages. In my mind at least this book’s lessons and themes ultimately contribute to its relevance to this age and I will concentrate more on these themes than the actual historical integrity of the book, which by the way is unassailable.

Firstly, it is a retelling of World War 2 history in the Indo-Pacific arena through the eyes of the two main characters Norah and Nesta who were captured and interned in POW camps by the Japanese and it is instantly hot, steamy and fraught. We’re not talking carnal hot and steamy, but the heat and steam that comes from fear, fright, violence, anxiety and the sheer worrying hell that only an intense armed conflict can bring. And it dumps you unceremoniously into the oceans and currents of fear and horror that parallel the straits that the titular sisters were cast into when the vessel they were on was mercilessly bombed by the Japanese air force. Typically, historical retellings of peoples and events are based on recollections and facts that in most instances are delivered with all the literary moisture of a tablespoon of Saharan sand. This is the first point at which Morris’ book distinguishes itself. She weaves the dialogue so expertly through and with the factual narrative that one is drawn into Norah’s rapidly changing world literally within the first paragraph. The resulting “story” is so compelling that it reads like an excellent work of non-fiction which is hard to put down and it took me only two days to voraciously devour it despite my schedule.

Secondly, it traces the history and character development of Norah, whose story we are introduced to first and the significant number of challenges she faces during the outbreak of the war, during her capture and her subsequent internment in the POW camps. Without giving away too much, she is separated from her parents who remain in Singapore and her beloved daughter Sally when she sends her away to Australia with her sister Barbara to escape the war. She then attempts to flee Singapore with her husband John and her sister Ena who leaves her husband Ken to look after their parents. The flight is not helped by John’s recent bout of typhus which makes the escape difficult to say the least. The boat they are on attempts vainly to escape the Japanese onslaught but they are sunk and are taken prisoner. Shortly after she and her sister are taken prisoner she is separated from John as they are placed in separate camps for men and women. But it is her development as woman during what is nearly three years and nine months of capture that is truly remarkable and the solace that she not only found in her music training but shared with all during what can only be described as hell, is not just unique in its carriage but hugely inspiring in its outcome. So Norah is dealing with an almost overwhelming emotional burden as her family is ripped apart along with having to deal with surviving the camp and its hardships as well as having to be a support to Ena, June (an orphaned 5 year old girl who bonds with Ena) and the rest of the female prisoners. Bear in mind that this character growth does not take place in a vacuum as Norah obviously interacted with almost all the other female prisoners for whom she came to represent a source of hope. It is in this period that the themes I alluded to earlier start becoming apparent.

Thirdly, Nesta’s story follows a parallel yet distinctly different path. Her story is simpler but not in any way diminished by the sheer magnitude of persona displayed by her. A physically small and delicate woman by description, her strength of character in the face of the ever-present threat of death at the hands of their captors, makes her an absolute giant and a literal tower of strength to all she was in contact with. Thrust into the leadership role with the death and brutal murder of the two matrons at the hands of the Japanese, she assumes the mantle reluctantly at first. By the time they are freed from captivity Nesta is a completely different woman who in every sense is emblematic of what is truly lacking in modern career women today. I’ll get back to this theme later.

The book continues to faithfully retell the hardships and experiences of Norah’s sister Ena, the orphaned June, the other two ladies who come to form an integral part of Norah’s inner circle (the formidable Mrs. Hinch and Margaret), the various nurses who look to Nesta for leadership, guidance and strength, the nuns who were interned with the women in the camps, their interactions and their interactions with their captors. It details the privations they suffered at the hands of the Japanese, their small victories in the face of their struggles and their individual growth and character development during this period, the truly horrendous sacrifices that women are forced to endure during times of war, but most importantly it chronicles the story of strength, growth, hope, perseverance, sheer force of will, inspiration and the formation and performance of Norah’s unique and hugely uplifting symphonic choir. And it was this choir that ultimately gave the women the upper hand in the face of their brutal captivity.

Now I’m not sure if Morris intended for the themes to be as strikingly evident as they are and if it is unintentional then it is quite simply a testament to her vast literary skill. As a keen observer of society and its changes, through Morris’s mastery I came to clearly see Norah as the true representation of what a feminist should be when compared to modern women. At once a soft, feminine, caring wife and mother without being unduly subservient, she became a symbol of strength, hope, courage and innovation to all those who were in contact with her. Notably all the women in the leadership roles (neither appointed nor self-assumed) fed off each other’s character and growth to become more of what they truly were. Strong independent women. And that in the true sense of what that term means as opposed to the current liberal woke, whiney, weak and self-entitled definition the world is saddled with at present. To juxtapose the two forms of feminism, Morris’ depiction and the woke view, would be to place a universe between them. On the one hand we have true feminine strength and character based on morals, values, traditions, faith and virtue and on the other (in this modern age) self-centered, braying, demanding, immoral, undeserving, idiotic entitlement. The comparison is beyond stark.

Nesta on the other hand becomes the literal poster girl for feminine leadership. As someone who is familiar with the different leadership styles, in my view Nesta came to epitomise the form of leadership that is the most difficult to emulate, that being servant leadership. Nesta’s form of leadership was characterized by humility and endless self-sacrifice. Simply put, her life for that period was lived for and in service to those nurses, women and children who were captive in the camp. To say that she excelled at it is a colossal understatement. She continued in this characteristic for the rest of her life. When searching for a modern or contemporary comparison I can safely state that she has no equal or at the very least, let me concede that I couldn’t think of any modern woman in a current leadership role to which I could make a comparison. If such a woman exists, then she does so far from the thoroughly jaundiced social and mainstream media platforms that tend to glorify the foul, purulent, active gangrene that is woke feminism. Feminist leadership today is a deadly toxic morass of ill conceived, unintelligent, self- aggrandizing, conceited self-centredness. It is totally bereft of true feminism, gentleness, empathy, servitude, compassion and most importantly, grace under pressure.

The nuns, who are led by Mother Laurentia and the encouraging dynamo that is Sister Catherina, quite literally keep the faith. Missionaries to Indonesian islands they become a spiritual bulwark against the Japanese and their accompanying evils. During times of great adversity it is not unusual for many to lose their faith in addition to their morals, values and hope in the fight to survive. That the sisters could be an encouragement and source of strength to all including themselves is another testament to the character, conviction, perseverance and beliefs of these incredible missionaries.

In the end it was Norah’s musical genius and the choir and concerts that flowed from it that bound all the women and children together into an unbreakable and clear show of resistance that also somehow drew even their captors in. Norah’s innovative symphonic choir brought out attributes, talents and appreciation that many of the women had long since buried or discarded and because it was so antithetical in the face of harsh captivity it became a source of an unbelievable hope that powered everyone through that period. The result of this choir is that it created another kind of choir. A choir of unity and co-operation amongst the women that saw them literally segue from one form of hardship to another without losing hope and faith in not just their faith but also in each other. And that Morris could convey this so eloquently and touchingly is a staggering achievement.

I am rarely moved by modern day literary works as they are quite simply banal and lacking. But this book was richly evocative and made me hearken for the days when women were truly women. Morris has quite unintentionally written the handbook for latter day feminism through her graphic and richly textured retelling of the hardships of women during war. And what separates it from the entire body of pseudo-intellectual hogwash that claims to underpin modern ‘feminism’ is that it is based on reality as opposed self-centred conceit, misandry and pure, misguided, hateful emotionality. Morris covers those attributes that truly makes women a prize and apart from the themes of feminism, true feminine leadership, faith and femininity she encapsulates all of this magnificently in one unspoken word. Grace.

A book like this is rare. The women it describes even rarer. It is even more rare for a book like this to wield the power that it does. It covers what is quite simply history and brings it to a modern, relevant and vibrant life that belies its origins and its true extent and relevance. I cannot recommend reading this book enough. And if you are a true bibliophile, this is a book well worth owning, not just because it is a historical book filled with lessons, but because for a modern-day society with no clue as to what a woman is, it is unintentionally the new feminist handbook.

Book review by Slartibartfast.